1 // Introduction

Velocity Based Training (VBT) is by definition a “form of auto-regulation of training, where day-to-day fluctuations can be accounted for by adjusting the training load” (Mann et al, 2015)_._

To break that down, VBT is a way to monitor an athlete’s readiness and ability to train via barbell velocity. If the bar is moving quickly, then the athlete’s readiness to train is high, and/or the load applied to the exercise is too low. If the bar is moving slowly, then readiness to train is low and/or the load is too high.

2 // What Is Velocity Based Training (VBT)?

VBT is a valid and reliable method of auto-regulation, which enables coaches to:

- Estimate an athlete’s 1RM

- Identify proper training loads when fluctuations in muscle performance occur as a result of life stressors

- Identify proper velocities and loads to train at to enhance specificity of training and monitor fatigue (VBT Zones)

- Receive immediate feedback on performance, ability and motivation of the athlete through velocity of the movement

(Mann et al, 2015)

3 // How To Implement Velocity Based Training

a) Measuring Barbell Velocity

First and foremost, you must have a method of tracking barbell velocity. This cannot be done through qualitative methods (i.e. your coaches eye), it must be through an actual quantitative method where data can be produced and assessed. This can be done with tools such as:

- With a Linear Positional Transducer (LPT), which is a central processing unit that calculates concentric velocity and power.

- With an Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU), like the Output Sports Sensor, which is a small wearable device with an integrated gyroscope and accelerometer that provides velocity values by using specific algorithms for each exercise.

NOTE: It is essential that the equipment is accurate, valid and reliable. If not, the data gathered is invalid and cannot be used in the prescription of exercise or RTP testing.

b) VBT Measurement Guidelines

Dr. Bryan Mann has been involved in the field of Strength & Conditioning since 1999 as a practitioner, researcher, and educator. He is also considered to be a world-renowned Velocity Based Training expert, and has created an easy to use guide for prescribing velocity and the rationale behind each, through the use of VBT ‘zones’, which is outlined below.

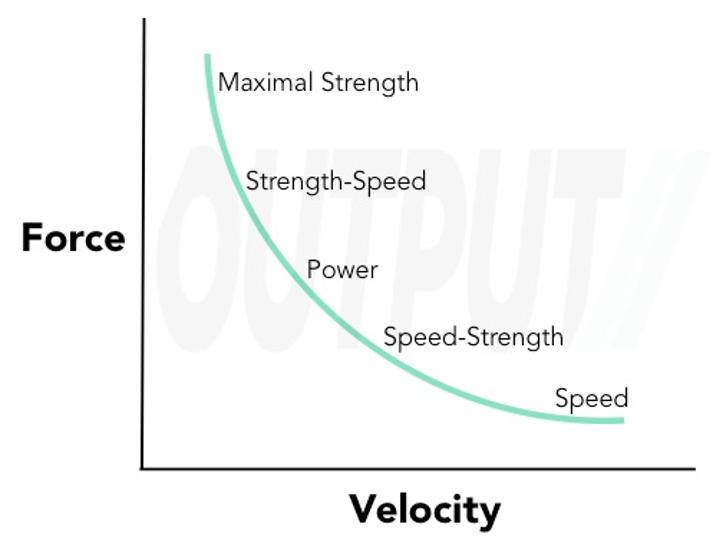

It is important to note that the zones are exercise and athlete specific. For example for the squat the 1RM is approached at around 0.3m/s and for the bench press is around 0.15m/s (González-Badillo and Sánchez-Medina, 2010). From this bottom range, absolute strength is developed until around 0.5m/s. The further velocity zones, and their respective ranges are outlined below.

- Speed (>1.3m/s): Moving a minimal load as fast as possible, so as to maximise speed.

- Speed-Strength (1.3 - 1.0 m/s): Moving a light load as fast as possible.

- Power (1.0 - 0.75 m/s): Moving a moderate load as quickly as possible. The priority here is on strength with speed being secondary.

- Strength-Speed (0.75 - 0.5 m/s): Moving a relatively heavy load as fast as possible. This will be a slow movement but it’s emphasized to move the weight as fast as possible.

- Maximal Strength (<~ 0.5 m/s): This is using a very heavy load, which ends up being a slow movement.

(Mann, Kazadi, Pirrung & Jensen, 2016)

c) Interpreting VBT data

There are many ways to interpret the data gained as a result of VBT. Many use VBT in performance testing, as rehabilitation markers and as a load prescription tool, to name a few.

Once the data is initially collected for an athlete, the accurate development of a load/ velocity profile can be made, and from that can be used to give a more insightful comparison of individuals, and their monitoring of changes over time. A more in-depth discussion on load/velocity profiling is coming soon.

The athletes minimal velocity threshold (MVT) can also be identified, which is the velocity associated with an athletes 1RM. MVT is exercise specific and remains stable even with changes in athletes 1RM over time. Therefore, knowing the MVT for a given individual and exercise allows for 1RM estimation using submaximal loads (Jovanović & Flanagan, 2014).

As stated previously, velocity profiling can help estimate daily readiness of an athlete, which can in turn be used to alter a training programme to suit how the athlete is performing on the day, which in turn helps to avoid injury. Due to its immediate feedback it can also be helpful for identifying and targeting specific training qualities, such as fatigue and exertion, and has also been shown to motivate athletes to apply consistent maximal lifting effort which in turn has been associated with positive training effects (Randell et al., 2011; Randell et al., 2011). To aid in this process, VBT zones can be identified in order to terminate a set when the mean concentric velocity of a repetition falls below that predefined value.

Other metrics, including range of motion (ROM) and bar-path, can also be very beneficial while measuring VBT. They allow for added feedback, particularly around an athlete’s technique and fatigue levels. For example: an athlete is performing a back squat within their normal VBT zone, but they are not performing the squat through their full range ROM. This could be due to a number of things such as injury, or fatigue. By monitoring their ROM, it gives the coach more information on the current state of the athlete.

S&C coaches are creating a culture of accountability and intent in their weight-rooms with Output’s accurate velocity based training and novel angular-velocity based training modules.

4 // Conclusion

- Essentially, VBT is a way to assess an athlete’s readiness to train, assess and prescribe load, and ensure specificity of the exercise to the athlete, sport and season.

- There are 5 main ‘VBT Zones’, in which the coach must ensure that the zone they prescribe to their athlete is exercise specific, appropriate for the sport and time of the season.

- VBT provides immediate feedback to both the athlete and coach, ensuring they are training with adequate weight at all times. Thus avoiding injury.

- VBT should only be measured with equipment that is valid and reliable.

// References

- González-Badillo, J.J. and Sánchez-Medina, L., 2010. Movement velocity as a measure of loading intensity in resistance training. International journal of sports medicine, 31(05), pp.347-352.

- Jovanović, M. and Flanagan, E.P., 2014. Researched applications of velocity based strength training. Journal of Australian Strength and Conditioning, 22(2), pp.58-69.

- Mann, B., Kazadi, K., Pirrung, E., & Jensen, J. (2016). Developing explosive athletes: Use of velocity based training in athletes. Muskegon Heights, MI: Ultimate Athlete Concepts.

- Mann, J.B., Ivey, P.A. and Sayers, S.P., 2015. Velocity-based training in football. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 37(6), pp.52-57.

- Randell, A.D., Cronin, J.B., Keogh, J.W., Gill, N.D. and Pedersen, M.C., 2011. Effect of instantaneous performance feedback during 6 weeks of velocity-based resistance training on sport-specific performance tests. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 25(1), pp.87-93.

- Randell, A.D., Cronin, J.B., Keogh, J.W., Gill, N.D. and Pedersen, M.C., 2011. Reliability of performance velocity for jump squats under feedback and non-feedback conditions. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 25(12), pp.3514-3518.